King’s College London: “Digitising collections opens up whole new areas for research”

This content was written by Geoff Browell, head of archives and research collections in King's College libraries and collections.

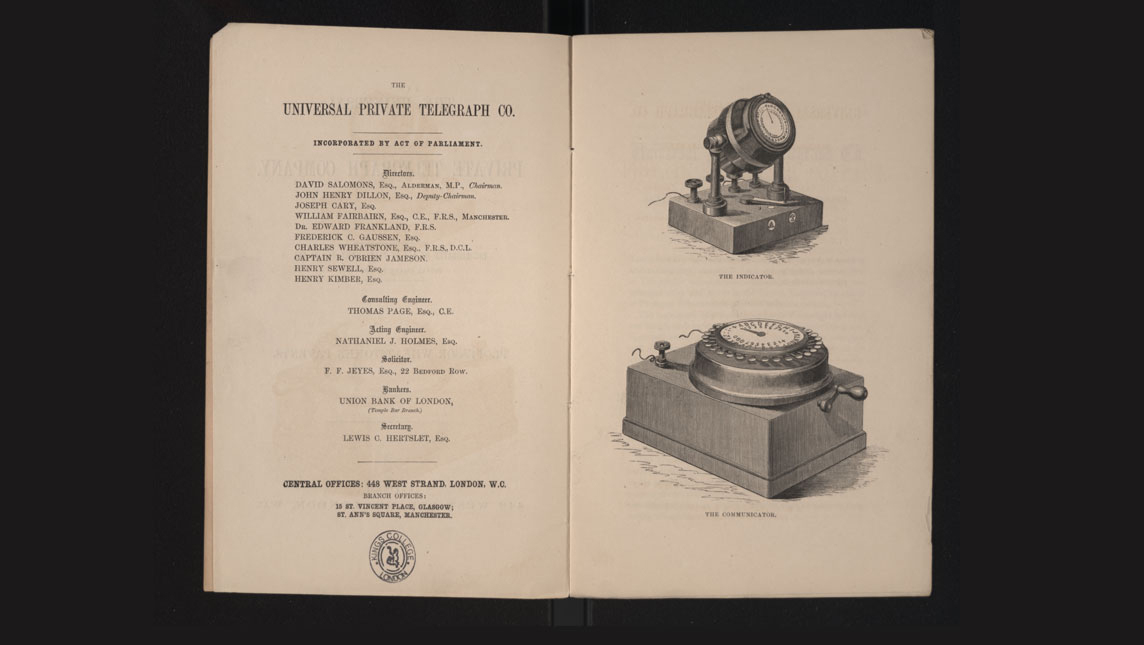

The UK’s researchers, learners and teachers now have free access to a new digitised collection of rare content from university archives and special collections. King’s College London’s Charles Wheatstone collection will be digitised as part of the project. The content to be digitised offers rich insights and opportunities to develop new avenues for research.

Archives are about people, not paper

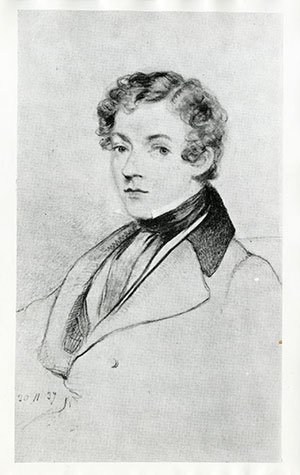

This is about enabling people to build stories. We’re hoping it will renew interest in Wheatstone as a man and in his science and his connections in London in the early and mid-19th century, because this was a critical time and place for scientific advancement.

Wheatstone was one of the century’s most renowned scientists and the professor of experimental philosophy at King’s. He left us his books, pamphlets, scientific papers and instruments. It’s thousands of items representing 19th century scientific thought. He worked on acoustics, electricity, stereoscopy (the beginnings of 3D imaging) and optics. He developed one of the first viable, publicly available telegraph systems.

His invention of paper tape for his telegraph made it much faster to send messages and this method was still relevant many years later, enabling the first computers to store data. He was a pioneer of undersea cables and cultivated scientific connections all over the world. He was a true polymath with interests that included music (he invented the concertina), philosophy, meteorology and even natural magic and parlour tricks. The collection brings this now largely forgotten man back to life.

Wheatstone was one of the century’s most renowned scientists. [...] The collection brings this now largely forgotten man back to life

As another portion of the project, we will be able to digitise part of the library of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), now the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office, which is one of our star collections at King's Foyle Special Collections Library.

My colleague Katie Sambrook, head of special collections & engagement, says

"The FCO Collection is our largest and most heavily used special collection, attracting researchers from all over the world. Its contents span 500 years of world history and many of the 80,000 books, pamphlets, maps, manuscripts and photographs it contains are held nowhere else. For this project we’re focusing on one of the richest areas of the collection, in terms of rarity and research potential: material which tells the story of the role of science and technology in the history of the British Empire.

"Botany, agriculture, the cultivation of crops such as tea, rubber and cinchona (for quinine); meteorology, including the effects of earthquakes and hurricanes; industrial exhibitions and trade fairs; infrastructure projects, such as the development of roads and railways; mining and other industries – these are some of the many themes that will be explored in the material we’re planning to digitise.

"In many ways this is a collection that tells the story of the making of the modern world, and we’ll be able to make this story available to researchers who might not be able to come to London to visit us."

Digitising collections opens up new research possibilities

The Wheatstone material includes notes and drawings on the back of advertisements and household bills. They give fascinating insights into life at the time, how scientific enquiry worked and how connections and networks operated in the area around King’s and The Strand. The area was already a scientific hub, where people were making scientific instruments and carrying out experiments, and there was a rich cultural life locally with The Royal Society, Royal Academy and various other academies all nearby.

The Wheatstone material [...] give fascinating insights into life at the time

Digitisation means these papers from our collections can be linked with other similar collections elsewhere and whole new subject areas for enquiry can be opened up. This is only really possible when collections are digitised so they can be compared and searched side by side.

Researchers working in the traditional way would need many lifetimes to visit all the countries and collections and do that work. One of the big advantages of digital is that you can do new and interesting things with the content and the data.

We’re particularly excited about digitising these collections because universities have generally focused less on humanities research in favour of science and engineering. We’re hoping this kind of project will help balance things out again.

Universities have generally focused less on humanities research in favour of science and engineering. We’re hoping this kind of project will help balance things out again

Working with Wiley and Jisc on this gives us confidence and access to resources that we don’t have enough of to do this work quickly ourselves.

We’ve been pursuing our strategic plan to digitise material to support learning and research but this obviously became suddenly more urgent in early 2020. Now, our library can’t do much of the face-to-face work we had been doing and there’s a huge push for online learning and teaching so we’re pushing digital content out to students.

Having the content available remotely is very, very useful because it saves us having to start from scratch. Working with Wiley and Jisc has condensed about ten years’ work into ten months.

Working with Wiley and Jisc has condensed about ten years’ work into ten months.

Sometimes it’s not that easy to get clearance to digitise and publish collections and there isn’t always the appetite to take the risk unless there’s some kind of umbrella. A project like this offers protection and gives us confidence that due diligence has been done.

Digitisation doesn’t replace the value of physical collections

Coming in and touching, smelling, feeling the original documents can really fire the imagination for those who are physically able to do it. Digital offers more people access to the content but seeing and handling the collections and talking to the conservators is still very valuable. It’s like the music industry. When digital came along it didn’t kill live concerts, they became more popular than ever. People want both.

When digital came along it didn’t kill live concerts, they became more popular than ever. People want both.

This collection is an output from our R&D project to develop sustainable approaches to digitising collections.

Jisc worked with academic publisher Wiley and several of our members to create this new history of science collection, inviting members to nominate parts of their collections to be digitised at no cost to themselves. This is the first time UK universities have had an opportunity to influence a commercial publisher’s decisions about what to digitise.

Browse the collection

The British Association for the Advancement of Science: collections on the history of science 1830-1970 is available free of charge to Jisc members through the Jisc licence subscriptions manager.

Image information: ©King's College London via Wiley Digital Archives: British Association for the Advancement of Science—Collections on the History of Science (1830s-1970s)